Four of us sat at a round table in the junior high school library – an algebra retake class in the heat of a New Orleans summer. A 100% humidity 100% of the time summer. Our forearms stuck to the textbooks, the round table, the mimeographed worksheets. We each brought a washcloth from home to wipe away our sweat.

Mr Martin was one of the nicest teachers around. During the school year he taught civics and history, but the principal had him teach algebra all summer long. Mr Martin made a dot on the green board and labelled it A. Then he erased the dot and the A and told us it was still there.

Our textbooks took pity on us and wilted a little. There was one fan in the room – the kind that didn’t oscillate. We took turns orbiting it with our washcloths.

Mostly, white kids went to other schools. I was in the 10% who didn’t go to private schools, or Catholic schools, or the one public school for supersmart kids who took an IQ test in order to get in. I wondered if those kids ever went to summer school, and, if they did, were their summer-school rooms full of air-conditioned air.

I didn’t understand what humidity really was until years later when I left New Orleans. Other towns were hot during the summer, but their summers didn’t swell into other months and their air didn’t swell so thick that each breath felt like you were trying to inhale a couch cushion.

You wouldn’t be wrong to say that algebra comes from zero. That’s what my summer-school teacher told me. Mr Martin drew a zero in the middle of the board. Then he added a long line on both sides and asked me to come up and draw a car at ground zero. I drew a circle with four little zero wheels. I drew windows and doors and labelled it VW. Mr Martin had a story about the car driving west into the negative numbers of Texas and east into the positive numbers of Mississippi, all to show me why multiplying two negative numbers creates a positive answer. I was lost on the highway, but no one could tell.

Everything is easier to set aside when it’s smaller, close to zero, where the possibilities are endless and sometimes mysterious.

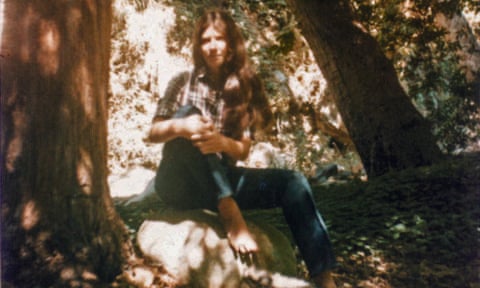

That summer-school summer, my mother set me to the side for five or six weeks – me on my own in our fourplex apartment with algebra homework, my 18-year-old brother out of the house, my little sister off with our father. My mother and her boyfriend were travelling out west, camping somewhere, across half the country. I knew the probability of her calling me from a camp ground was mathematically insignificant.

I carried her suitcase to her silver Honda Z. The tiny car had two cylinders and two doors and was the kind of car four men could pick up, the kind that ranked first in gas mileage during the 1973 Opec oil crisis. I put her suitcase next to his suitcase. Their tent, two sleeping bags, their snacks and maps and binoculars and cameras were all collapsed together in the back seat, all part of her summer disappearing act.

I remember asking my mother not to go on her trip. We stood in the living room on the green shag rug. “You’ll be fine.” She rolled her eyes. “Teenagers love being on their own … you’ll see.” Then she smiled. “You won’t even want me to come back.” I stared at her suitcase and nodded.

My mother didn’t know that I wrote my name and my favourite number eight in black Magic Marker on the bottom of her shoes before she took off. She couldn’t see my name on the black soles, but it was there, touching the ground with her, wherever she was, around, somewhere. I may not have had a number to reach her, but I was sure she could feel me.

The silver flash of car, her hand leaning out of the driver’s window, her moonstone ring catching the light as she waved goodbye.

First, I tried naming the knives in the kitchen after the kids I babysat for: Cathy, Bill, Todd, Maggie. But still they looked dangerous – ready to defect with the first intruder who broke through the little lock on the apartment’s front door. Even if they remained loyal, one slip through tomato pulp to the thumb bone and who will fix this all-alone mess? Who will drive this mess to the hospital?

Not having an insurance card equals having no insurance. Hospitals require someone who can sign for things. So, I hid the knives – boys under the stove, girls in the freezer.

The lock on the front door of the apartment was the simple kind, the twist button in the middle of the doorknob kind. The kind you can open with a butter knife in the keyhole or a school ID card pressed between the lock and the door. The back door had the serious kind of lock, the dead-bolt kind. I was a fan of that dead bolt.

I’d seen Mary Tyler Moore’s character Laura Petrie improvise a makeshift alarm system on the Dick Van Dyke Show. She was a mother in her 30s and still she was scared when home alone for one night. So, she piled pots and pans in front of the door. That way, if someone broke the lock and opened the door she would hear the crash and be able to get a head start. She was babysitting the neighbour’s pet parrot and the parrot kept saying, “Don’t be scared. Don’t be scared.”

I was groomed for the task of Don’t Be Scared. I learned Don’t Be Scared the way free divers learn Don’t Breathe In as they swim headfirst into the blue-black sea with only a wet suit and a face mask. No tank of air is strapped to their backs. No nothing but the air they carry inside.

You sink or swim in this world. That’s what my mother told me again and again.

Sometimes that summer, I went into my mother’s closet and looked around at her clothes still there. Sometimes I wore one of her brand-new shirts because I liked new clothes, and she wasn’t home. I liked to turn all the way around in the closet and let my cheek brush against the crowd of rayon, silk and cotton shoulders. I didn’t go in looking for it, but I knew somewhere in between all the shoulders hung my worry: will she come back?

There was some money in the envelope my mother left in the kitchen drawer for groceries and the occasional cheeseburger. It was 10pm on a Thursday night and I could go anywhere. There was a chance the K&B drugstore on Saint Charles Avenue and Broadway would still be making cheeseburgers.

I hadn’t done much of anything the day before, the Fourth of July, except babysit for Maggie. Summer school had closed for the holiday, and Mr Martin and the other summer-school students and Maggie’s family and my mother and her boyfriend and everyone had been somewhere looking at fireworks, spread out on blankets, with dogs and kids running around, music playing. A mile walk to the K&B on the day after the Fourth for a cheeseburger and cola seemed like a small thing I could do.

Saint Charles Avenue was the most famous avenue in all of New Orleans, with streetcars travelling back and forth on the grassy neutral ground, and where rich people you never saw showed off houses that looked like sugar. I felt I was safe on Saint Charles, even if the sidewalks were dark with tree shadows.

But a forest-green pickup truck circled around several times – into the neutral ground, across the streetcar tracks and back around to pass me on the sidewalk again – his red hair, red neck, him looking at me.

I crossed the avenue once or twice to lose him the way I’d lost other men on other days. I thought it had worked until there was the man outside his truck, standing on the dark sidewalk not far from me. He asked me for directions to the fireworks at Lake Pontchartrain since he was from out of town. It was 5 July, and the fireworks were over, and I didn’t know the directions anyway. I turned to walk away, and he grabbed my arm. I was one block away from the K&B on the corner.

I saw the knife in his hand down by his side. I froze the way an animal might freeze right before being killed. He said: “If you move or scream you are a fucking dead duck.”

The way fuck and duck rhymed. He pulled me closer to the knife aimed at my guts. The way my guts made a fist.

The world split open and wobbled. The way I was sure someone driving by could see this and stop this. The way no one could see this knife by his side. He promised he’d kill me if I made any sound as we walked arm in arm to the narrow sidestreet and his truck parked in the dark.

The way I should have jumped out of his truck while he was driving away. But who would help me after I jumped? He’d get to me first and kill me right then. The way I wanted to Not Die and felt like I was dying.

The way I calculated how many days from Thursday it would take before someone would miss me. Maybe by the middle of next week, after enough summer-school absences, five days away. But no one would be home to get a call from the school office.

He wanted to drive to the lake or maybe across it to Mississippi. What were the chances he would bring me back here? He said he hadn’t decided if he’d kill me or not. The way I bargained and he unzipped his pants and made me touch his pink dick. The way I persuaded him to stay uptown and rape me in the park. That way, if I got away, I was still close to home. That way, if I didn’t and he dumped me dead in the lagoon, someone I knew might ID me the next day. Then when my mother came back, she’d know I hadn’t just run away. And I, as a dead girl, wouldn’t feel so all alone in the endless dark sky.

The way I heard someone walk by as I took off my clothes inside the dark truck. Who walks in this park so late at night? Who would believe this was a rape taking place? The way this rape could get worse if I shouted right now. I turned very small. He still had a knife, and the footsteps went away, and my silence stayed with me, and he thanked me right then for being on his side.

The way my arms kept pushing him away without thinking. The way I cried, and he said: “Do I have to tie you up?” The way I said: “No.” He took over my body while I waited on the moon. The way I floated for hours on the dark side of pain. You sink or swim in this world. The way I sank. The way I swam.

“You were no virgin,” he said after. “There’s no way you are just 14 years old.” I nodded, because that’s what you do when you’ve been raped by someone who still might drive off to Mississippi with you in their truck. Someone who still hasn’t decided if he’s going to kill you or not. Someone who needs to believe that this was no rape, that you are not 14, that there’s no way you’re a virgin.

We drove around the park while he pretended we’d been out on a date. I nodded, because that’s what you do when a date with a rapist is better than a trip to Mississippi with one. The way I thanked him for the date.

He kept driving around the park and uptown and past Tulane and Loyola and back to the park, pretending and deciding.

Tell me if you’re going to call the cops so I can be ready, you know, to get out of town sooner.

I wouldn’t I wouldn’t I wouldn’t. Why would I? The way the policemen would want to reach my unreachable mother.

The way he let me open the truck’s door at the next corner and go. He asked for my name, and I gave him someone else’s. The way I ran a kind of limping, hobbled run the six blocks home.

I left my shoes and underwear on the floor of his truck. Two men on the sidewalk shouted something at me. The way I hated them. I looked back to see if they were chasing me, if the truck was circling around for me. The way pain shot through me as I ran, and blood dripped down my legs and soaked the crotch of my pants. The way I bled for three days.

That Thursday night, for the first time, I piled three silver pots and some glass ashtrays in front of the door, like Laura Petrie did on the Dick Van Dyke Show. I began my practice of laying my head where my feet used to go, so I could see through the living room to the big front door with the too-little lock and my homemade alarm. That way I could sleep until it came crashing down.

There’s a tiny speck at the corner of the eyelid near the bridge of the nose and it’s called a punctum. When I was in grade school, I held an onion near my face while I looked in the mirror and pulled down my eyelid. I waited for my tiny speck to produce a stream of onion tears. Turns out that tears do not come from this miniature orifice. Instead, the punctum is a drain for tears that naturally fill our eyes all through the day. When we cry, the small drain becomes overwhelmed. Our eyes are not suited for a flood of sad feelings.

I forgot to bring my washcloth. I forgot to bring my book. I sat in the school library surrounded by numbers and books and felt the feeling of nothing, like the space inside zero that holds everything together. I put my head on the wooden table and listened to Mr Martin go on about numbers. He drew a large oval on the green board and in it he wrote rational numbers. Then he drew another oval next to the rational one and wrote irrational numbers. I didn’t think about numbers. I thought about the ovals Mrs Harrigan had drawn on the green board during health class last year. Inside the space of the ovals she’d written the word impregnated. Then she lectured us on the importance of guarding our eggs at all costs.

Please let me be not impregnated. I prayed to all the infinite numbers in the universe. I prayed to the moon, to the top of the trees and the lagoon in the park and to the school that I sat in full of summer-school teachers. I covered every space I could see with my one single prayer. Please let me be not impregnated.

I stayed after class and helped Mr Martin sort through his papers. Wouldn’t he see the things my face had to say? Then maybe he’d bring me to his house where I would babysit his son and help out his wife. She might comb my hair and make me a sandwich and let me sleep on their couch where it would feel so much safer. They would hear my telling and keep my secrets. And I’d go back home in August when my mother returned.

I hinted. I talked about the recent case of a teacher in another school who had been raped in the parking lot by a man she carpooled with.

“That kind of happened to me,” I said. “Last night.”

I held my breath like a diver.

Mr Martin didn’t look up from his papers. He reached for his briefcase and put his notebooks inside.

“Men can’t understand rape,” he said.

When I got home from school, I put the Thursday clothes in a paper bag and took them to the trash can in the parking lot behind the apartment building. They’d have to wait there until the trash was picked up on Monday. But when I got back upstairs, I could still hear them crying. After an hour, I brought the clothes inside.

I washed them by hand and then hid them under a box at the back of my closet. It was the best I could do. They quieted down or else they just died.

At night, my ears were two bloodhounds without a leash following every sound. There was a faint clicking that took me a week to locate. I’d looked everywhere for its source. I even timed the intervals between the clicks – 20 seconds, six seconds, 12 seconds. The pattern repeated, but I couldn’t break the code. Then one morning as I waited on the corner for the light to change, a clunking sound hung above me and I looked up: 20 seconds of green, six seconds of yellow and 12 seconds of red.

I brought the Random House dictionary into my room. I wondered if other people picked words at random from dictionaries and books to help them find answers they couldn’t find elsewhere.

I let the pages of the large dictionary flip-flop back and forth between my palms. I wanted a word just for me in that moment.

The pages fell open in the As. I closed my eyes and let my finger land on a word.

ag·gra·vat·ed

adjective

an offence made worse, as in the use of a deadly weapon [kid-napping, rape]

I couldn’t let that word stay in my room overnight. Some words that show up are not talismans at all. Instead, they push their way forward like a bad dream with a fever.

I was sitting in algebra class when the blood came. Mr Martin was in the middle of reading a quote about algebra being metaphysical. The VW zero we’d drawn was still in the middle of the east-west highway behind him. I asked Mr Martin for a pass to the girl’s restroom.

Dear Our Lady of the Blessed Menstruation, thank God I’m not pregnant.

Mr Martin had no idea what a horror the girls’ restroom was – how not a single toilet worked, ever. How the toilets were chronically stopped up with bloody Kotex and shit. How, during the regular school year, the girls’ bathroom was just a place to buy dope, write graffiti, smoke, fight or fuck. I felt like I might vomit.

During summer school the bathroom was mostly empty. I jammed my washcloth into my underpants and headed home. For each block on the long sweaty walk, I counted how many humid breaths I inhaled and exhaled. Counting this way kept me from fainting.

The cramps were furious – as though my uterus was slicing its own lining to shreds first before spitting it out. As though the lining were the underpants I left in the truck on Thursday 5 July. As though my pelvis was finally able to scream and kick and punch the closest thing it could find.

It never occurred to me that it should have occurred to my mother to do more to protect me. What you get is what you get.

My mother wasn’t the kind of person to need other people. That’s what she told me once when I was alone in Ireland at 18 years old. I was ready to come back after three months on an independent study project for college. I didn’t use the word lonely, but my mother could sniff out my soft sides like a German shepherd sniffs out a bomb. I only ever told her I missed her one time after I’d moved out. She howled in complaint. “How can you miss me? You keep coming back.”

After I graduated from college, I moved to New York City. So Big and So Fast. I uprooted my fear and never moved back to my home below sea level.

I worked with heroin addicts in a methadone clinic on Third Avenue in Brooklyn. The clinic was in a squat brick building that sat under the elevated expressway alongside cheque-cashing joints and scrap-metal shops. It was 1980 and everything was grimy. The clinic had no windows, just bricked-in square sockets missing their square eyes. Inside the front door sat a uniformed officer with a gun on his hip. But I liked working there.

The clients served as an antidote for my own predilections. Their trauma flooded through the clinic and kept my own trauma at bay. The first client I met in the clinic was Louis, a young guy my own age who tried hard to get clean. He dressed sharp every day and smelled of cologne. A Bengal tiger tattoo crouched at the crook of his arm, covering his troubled cradle of veins.

More than a third of adolescents who are abused or neglected will have a substance abuse disorder before they turn 18 years old. I took it hard when Louis disappeared. I took it hard when I learned that he had relapsed and was dying at home alone from a disease we’d soon learn to call Aids.

The Guardian Angels had just begun patrolling the subways when I moved to New York City. They wore red berets and white T-shirts. The only weapons they carried were their martial arts skills and a cool logo bearing guardian wings. I decided to find a martial arts dojo in my Brooklyn neighbourhood and begin my own training in earnest. Most days after work, I headed over to the dojo eight blocks away.

The temple is a vulnerable spot on the body and I learned how to exploit it with a fast stab from an ink pen. I knew how to smash a nose with the heel of my hand and jab an eye with a finger turned bayonet. Everything can be made into a weapon somehow. The point is to shock the fucker and create enough space to just run away.

Several women in the dojo posted a manifesto in the dressing room and asked the other women to please sign the pledge: “I promise that should anyone ever attack me and try to rape me, I will always fight back with everything that I have, even if it means a fight to my death.” As though our martyrdom will be remembered and hailed in the future, our faces commemorated on postage stamps, and our sacrifice observed annually with large wreaths of white flowers. Because not fighting to the death marks you for life as some kind of traitor. I watched as students left the dressing room taller by a foot after making a promise to one another to never be me.

We’ve always had ways to describe the suffering that continues after nearly losing your life. Soldier’s heart was the term used to describe post-traumatic stress disorder among civil war veterans. Shell shock and battle fatigue were for veterans of fresher combat.

Only recently have we realised that rape is the longest-running war on the planet.

I don’t remember the exact day my mother came back home from her summer road trip. But I know it was after I passed summer-school algebra because I signed her name on my report card with big swirling loops the way she would have done. And I know it was after the Watergate hearings went off the air on 8 August because she missed the whole thing, and I no longer came home in the afternoon to watch it live on our tiny Sony TV. I don’t remember having to rush around and clean up the apartment. I always kept the dishes washed, the rugs vacuumed, the plants happy and the bathroom clean.

I don’t remember the day my mother returned, because she left again the following summer for five or six weeks, and that’s what sticks out. But I can imagine my mother’s silver Honda Z pulling up to the kerb in front of our apartment with all her stuff in the back seat. And I imagine, if I was home, I helped carry all her things back up to our place.

I don’t remember, but I guess she had stories to share about the desert and the thousands of stars you can see in New Mexico when you’re camping at night, and how she’d still like to fly into outer space if she had a rocket. I imagine I helped my mom pack and unpack her silver Honda Z again the next summer.

One of the astronauts said that when they went to the moon, they were technicians, but when they returned to Earth, they were humanitarians. He was talking about the power of the big picture, the connections you can see from up and over, that view you get when you float in space like a dead man and look back at your home.

My mother went to New Mexico and then to Minnesota and around somewhere, but I was the one who got the long-distance view. And just like the men who walked on the moon, I tried to love the whole world and its magnificent desolation, even if it killed me.

This is an edited extract from Everywhere the Undrowned by Stephanie Clare Smith, published by the University of North Carolina Press at £19.95. To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.